6 September 2021

In the past 18 months there have been an unprecedented number of news stories, press conferences, blogs, and social media posts relating to “COVID-19” and the reported single cause of this ethereal disease: the alleged virus “SARS-CoV-2”.1 It’s not always clear that the meaning of the word virus is actually understood — certainly not by politicians and public health bureaucrats, but perhaps of greater concern not by many medical practitioners either. Early on in the corona crisis when I would ask questions about the proof of existence of SARS-CoV-2, my medical colleagues would send me a one sentence message saying, “proof is here” with a link to a site like GISAID.org2 (which purports to show the viral “genomes”) or a paper claiming to demonstrate “virus isolation”.3 I spent some time going over the various papers they sent, read a couple of textbooks of virology, and was left wondering whether most of my colleagues were just reading the headlines.

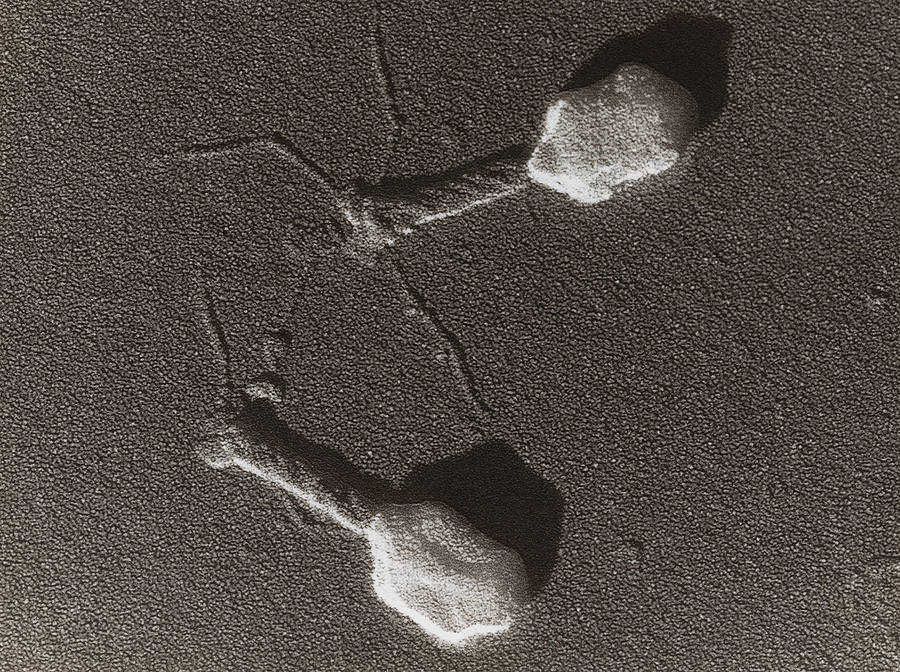

Perhaps the problem starts early in a doctor’s training where despite most medical schools teaching significant amounts of microbiology, very little time is dedicated to virology, outside of the clinical syndromes that are alleged to have monocausal viral aetiologies. Additionally, the virological theories themselves are generally presented as established facts. By the time of graduation the majority of doctors could be forgiven for thinking that pathogenic viruses have been seen in nature, or found in diseased tissue, and that the typical “virus” looks like a bacteriophage (a type of virus that is usually claimed to parasitise a bacterium by “infecting” it.)

Source: https://i.imgur.com/RyGpIQZ.jpg

Bacteriophages (and “giant viruses”) are unique among viruses in that they can be seen and isolated in nature, often from sea water where they can be found in abundance. The number of bacteriophages on the planet is astounding: it has been estimated that there are more than 1031 bacteriophages, more than every other organism on earth combined.4 When scientists began researching bacteriophages they concluded that their appearance around bacterial cells in test tubes indicated that the bacteria were being “attacked” by the phages and they were gaining entry then replicating themselves inside the cell.

However as microbiologist Dr Stefan Lanka explains they were looking at the phenomenon in a backwards way: “It was only later discovered that merely the bacteria which had been highly inbred in the test tube could turn into phages themselves, by contact with phages, but this never applied to natural bacteria or bacteria which had just been isolated from their natural environment. In this process, it was discovered that these ‘bacterial viruses’ actually serve to provide other bacteria with important molecules and proteins, and that the bacteria themselves emerged from such structures.”5 So what has been viewed in a pathological light, actually appears to be nature propagating further life in response to environmental stressors. Unfortunately however, mainstream virologists subscribed to the pathological model as Dr Lanka goes on to explain: “Before it could be established that the ‘bacterial viruses’ cannot kill natural bacteria, but they are instead helping them to live and that bacteria themselves emerge from such structures, these ‘phages’ were already used as models for the alleged human and animal viruses. It was assumed that the human and animal viruses looked like the ‘phages’, were allegedly killing cells and thereby causing diseases, while at the same time producing new disease poisons and in this way transmitting the diseases. To date, many new or apparently new diseases have been attributed to viruses if their origin is unknown or not acknowledged.”5

The word virus derives from the Latin virus meaning poison or a potent juice. The meaning “agent that causes infectious disease” emerged by the late 1700s and the modern scientific use dates to the late 1800s.6 Russian Botanist Dmitri Ivanovsky is alleged to be the discover of viruses in 1892. He performed experiments with “infected” sap to show that tobacco mosaic disease could be transferred between plants.7 The “infected” sap was passed through Pasteur-Chamberland filters which were known to filter out bacteria so when the filtered sap caused other plants to become diseased, it was concluded that there was an even tinier infectious microorganism responsible. Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck used the term ‘virus’ for the postulated new type of microorganism in 1898.8

The invention of the electron microscope in 1931 allowed visualisation down to a tiny fraction of this size that had been permitted by light microscopy, so for the first time it was theoretically possible to see viral particles. Soon afterwards researchers began claiming that they had identified various viruses with this new technique “confirming” the theories of the earlier virologists. But are these nanoparticles viruses by the actual definition of the word?

Source: https://visualsonline.cancer.gov/details.cfm?imageid=2257

In the modern era, the textbook of Molecular Cell Biology, 4th edition defines a virus as, “A small parasite consisting of nucleic acid (RNA or DNA) enclosed in a protein coat that can replicate only in a susceptible host cell”.9 This is where the definitions are crucial. Parasite implies that the organism harms the host in order to obtain its required nutrients and make more copies of itself. The textbook goes on to explain that, “once it infects a susceptible cell, however, a virus can direct the cell machinery to produce more viruses. Most viruses have either RNA or DNA as their genetic material.” From this we can conclude that in modern terminology it is implied that a virus is a tiny parasite consisting of genetic material (its “genome”) surrounded by a proteinaceous shell that infects susceptible host cells and harms them (creating disease).

In the 20th century there was more emphasis on trying to purify suspected viruses through techniques such as nano filtration and sucrose density gradient centrifugation with confirmatory electron microscopy.10 Purifying these particles is a vital first step so they may be formally characterised in terms of their structure and biochemical characteristics. In the 21st century the virologists appear to have given up on purification and thus true attempts at isolation of the alleged viruses. They claim that indirect techniques such as observing in vitro cytopathic effects, massive parallel sequencing of crude specimens with synthesis of in silico “genomes” and the PCR are sufficient to provide “evidence” of the supposed offenders. We outline the problems of drawing conclusions from these indirect techniques and the derailment of virology over the past century in Virus Mania.

Going back to the electron microscopy images — how can the nature of these observed nanoparticles be determined? As stated in an article that appeared in the journal Viruses in May 2020: “Nowadays, it is an almost impossible mission to separate EVs [extracellular vesicles] and viruses by means of canonical vesicle isolation methods, such as differential ultracentrifugation, because they are frequently co-pelleted due to their similar dimension. To overcome this problem, different studies have proposed the separation of EVs from virus particles by exploiting their different migration velocity in a density gradient or using the presence of specific markers that distinguish viruses from EVs. However, to date, a reliable method that can actually guarantee a complete separation does not exist.”11 It is not clear how the authors would know what they are trying to separate: the nature of the particle (i.e. if it is infectious or pathogenic) cannot be established simply by observing it under the electron microscope as unfortunately they don’t come with any labels.

Identifying a nanoparticle that has some genetic material surrounded by a protein shell only partially fulfils the definition of a virus. In order to see if the particles are able to infect and cause disease in a host there needs to be another step in the process. This is in the form of clinical experiments where these purified particles alone would need to be shown to cause disease in an organism that has been exposed to them. After all we are told that “infections” such as influenza and COVID-19 are so highly contagious that viruses travelling on invisible droplets in the air are able to pass from host to host with the greatest of ease. Shouldn’t this be very easy to replicate with other “viruses” in an experiment? Simply aerosol the purified (as best they can) viral particles into a confined area such as an animal’s cage and they will quickly show signs of disease which they will then pass on to other animals. If anyone has seen such a study, I would love to see it!

Please note:

Papers such as “Airborne Transmission of Influenza A/H5N1 Virus Between Ferrets”

don’t even show the existence of a virus – they used mixed cultures

with indirect techniques and no ferret showed any signs of disease until

they injected the mix directly into the animals’ tracheas.

Papers such as “Newly discovered coronavirus as the primary cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome” do not, “fulfill the criteria required to prove that SARS-CoV is the primary cause of SARS,” as outlined in my video, “What Happened To SARS-1?”

References:

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19

2. https://www.gisaid.org/phylodynamics/global/nextstrain/

3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32080990/

4. https://health.ucsd.edu/news/releases/Pages/2017-04-25-novel-phage-therapy-saves-patient-with-multidrug-resistant-bacterial-infection.aspx

5. https://wissenschafftplus.de/uploads/article/Dismantling-the-Virus-Theory.pdf

6. https://www.etymonline.com/word/virus

7.https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/apsnetfeatures/Documents/1998/ZaitlinDiscoveryCausalAgentTobaccoMosaicVirus.pdf

8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC241285/

9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21607/#A7862

10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC380491/pdf/applmicro00046-0194.pdf

11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7291340/

The Yin & Yang of HIV - Part Three:

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário