David Montoute

April 28th

Following the defeat of presidential candidate Marine Le Pen on April 24th, a barrage of press articles has explained the re-election of the spectacularly unpopular Emmanuel Macron in predictable terms. Thus, for the Daily Mail, Macron was re-elected President of France by voters who "held their noses" and opted for the presumed "lesser evil". The "greater evil" of Marine Le Pen's Rassemblement National (formerly the Front National) has typically been "blockaded" in the second round of voting by the rallying together of pro-EU establishment parties. This year, Jean Luc Mélenchon’s call to his voters to "not give one single vote to Marine Le Pen" was an acknowledged factor in the second round result. And so too was second round voter turnout, the lowest since 1969.

However, a window into France's general discontent and increasing atomisation can be seen in the fact that no sitting French president had been re-elected in the previous two decades. In the first year and half of Macron's rule, the Rothschilds banker rammed through business-friendly reforms, including tax cuts for the wealthy, and confronted the country's strongest unions over the weakening of France's labour codes, which made it easier to hire and fire workers. As purchasing power collapsed, the country saw the biggest strikes in years and Macron acquired the status of the country's most unpopular president of all time. During this same period, relentless Yellow Vest protests were brutally suppressed, and soon afterwards there followed one of the most severe and totalitarian lockdown regimes in all of Europe, whose economic effects drove France's trade deficit up to a record 84.7 billion euros. The vaccine pass and health pass mandates also led to tens of thousands of firefighters, nurses, police and, soldiers being suspended without pay, which in turn brought hundreds of thousands of people to the streets in sustained, weekly demonstrations across the country. Rubbing salt in the wound of his Covid Gestapo tactics, Macron added in January that he really wanted to piss off (emmerder, lit. "cover in shit") unvaccinated French people, a vulgar jibe that drew protests from across the political spectrum. As the presidential elections approached, a fresh corruption scandal broke, as it was revealed that Macron's government had awarded consultancy firm McKinsey (one of the architects of France's 'health pass' policy) €2.4 billion in fees since 2018. This occurred whilst the company was being investigated for dodging corporation tax in France over the period of a decade.

Yet, in spite of the incumbent's unprecedented unpopularity, the major polling companies unanimously forecast a Macron victory in April's elections, a forecast that was fulfilled by an even greater margin than expected (58.55% to Le Pen's 41.45%).

The result appears more surreal again when we consider how, on April 5th, just four days before the first round of the presidential election, the Consumer, Science & Analytics company carried out a survey for CNews by asking a key question: "Do you want to change the president of the Republic?". In this richly detailed survey, 66% of respondents wanted a change of president. This overwhelming rejection of the incumbent was confirmed by other surveys. The French radio network RTL carried out an online survey on March 4th which showed that 84% of the respondents (consisting of more than 42,000 people) did not want Emmanuel Macron re-elected. RTL soon deleted the study which was released on Twitter but later published another poll revealing an even greater level of rejection (of 91%).

On the same day as the initial RTL survey, Le Figaro published its own poll in which 90% of their 32,000 respondents were left "unconvinced" by Macron's programme, which had been broadly outlined in an open letter carried by regional newspapers.

Could it be that Marine Le Pen, who is no longer perceived as "far-right" by a majority of French people, was truly deemed too toxic to replace Emanuelle Macron? Several events during the election night, and in the days leading up to it, suggest a different truth.

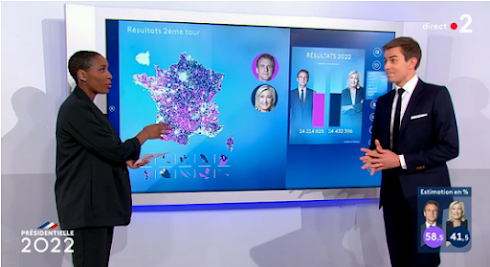

On election night, the channel France 2 presented results “directly from the Interior Ministry”. At around 10 p.m., public television gave Marine Le Pen more than 14.6 million votes, as seen here:

https://twitter.com/i/status/1518362221105004544

This put Le Pen slightly ahead in the count, only to go down by over a million votes while Macron pulled ahead by 4 million. So how did Marine Le Pen manage to go from 14.6 million votes around 10 p.m. to 13.3 million votes an hour later? This was enough to generate rippling claims of a fraud that mainstream media summarily dismissed.

The TV channel in question attributed this gross inconsistency to a "computer error" which had led to the dissemination of "overestimated" results compared to those provided by the Ministry of the Interior, an explanation that the Associated Press happily regurgitated. The France 2 apologised and said its software had mistakenly counted some regional votes for Le Pen twice. But why this "glitch" affected only Le Pen's votes and not Macron's remains to be answered. Could it be that France 2 was connected to a raw data stream before the Interior Ministry's recomposition?

The website Qactus (via Europe Reloaded) drew attention to the improbably accurate estimates of the second round score at 8 pm. At this point, 5 hours before the final results were revealed, only 4% of the results at the polling stations were known. We can therefore legitimately wonder, said ER, if the results were not already known in advance.

That Macron's "victory" was a foregone conclusion is also suggested by the an early "mistaken" announcement of Macron's victory by the BFMTV, France's most watched news channel. The announcement came at 6.30pm, more than 6 hourse before the final results.

Éric Verhaeghe also pointed to Macron having lost 2 million votes compared to his 2017 result. In this context, the essayist said, serious questions about Le Pen's "defeat" need to be asked.

In an apparent reprise of 2017, video reports also began to circulate of torn (and therefore invalid) Le Pen ballot papers. In an officious "debunking" exercise, France 24 cited anonymous "experts" to sustain their claim that the damage evident in the clips was insufficient for the ballots to be declared invalid.

All of this comes on top of further confounding factors, such as the recurring problem of automatic deregistration of voters who had changed addresses.

According to official statistics, this process accounted for nearly

227,000 voters who were unable to vote in the first round of the

election.

The airbrushing of all of these events from mainstream discourse has done nothing to pacify Le Pen's voting base, 30% of whom already believed the election was rigged prior to the second round. French electoral law stipulates that only a candidate (or a representative of the State) can contest the results of an election after the closing of the polls. Yet despite the abundance of red flags here, Le Pen herself has not contested the results. Marine's general strategy during this campaign involved a mainstreaming of her brand, dropping her longstanding aim of withdrawing France from the European Union and softening her overrall image. Whilst much of this was clearly tactical in nature, the RN leader's quest for 'respectability' was brought into sharp relief with her tepid and ineffectual opposition to Macron's lockdown regime. For many, she began to appear as "just another establishment politician".

Meanwhile, protests erupted across the country in response to Macron's "victory" and the President was pelted with tomatoes upon his first public appearance after the election. The likelihood of a return to Covid "health" restrictions, as well as France's central participation in NATO's economic sanctions, ostensibly directed at Russia but in reality targeted at the economies of Western Europe, will inevitably aggravate popular rage towards Macron. So acute is France's social fragmentation now that Chinese academic Wang Yiwei's recent prediction of an approaching revolution does not appear far fetched. The nation's abrupt awakening to the possibility of election-rigging, on full display across election night TV screens, may well constitute the necessary trigger.

But France is hardly a unique example. Pointing to the clearly rigged 2020 US election and the dubious UK election in the year prior, Off-Guardian posed the pertinent question of whether elections mean anything at all in the context of the Great Reset. Given the breadth, and ambition of this corporate fascist endeavour, would the global elites really leave to chance the election of national leaders in a "core country" such as France ?

The question seems to answer itself. And it places true oppositional strategies in an entirely new context.

***

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário